Many-to-Many: The Messy, Meta-Process of Prototyping on Ourselves

Welcome back to our ongoing reflections on the Many-to-Many project. In our last three posts, we’ve taken you through the journey of building our digital platform — from initial concepts and wrestling with complexity to creating our first tangible outputs like the Field Guide and Website. We’ve shared how the project’s tools have emerged from a living, iterative process.

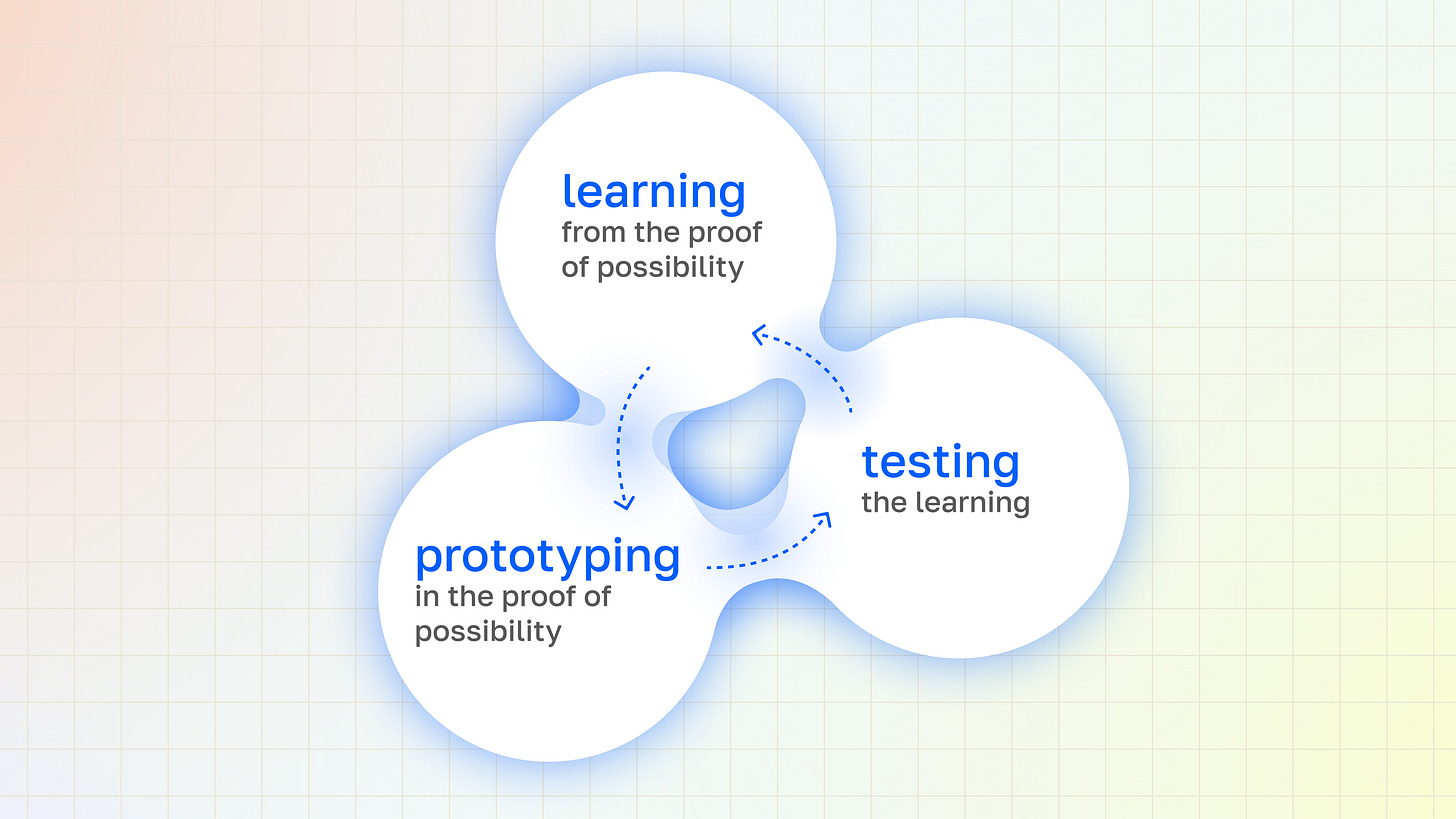

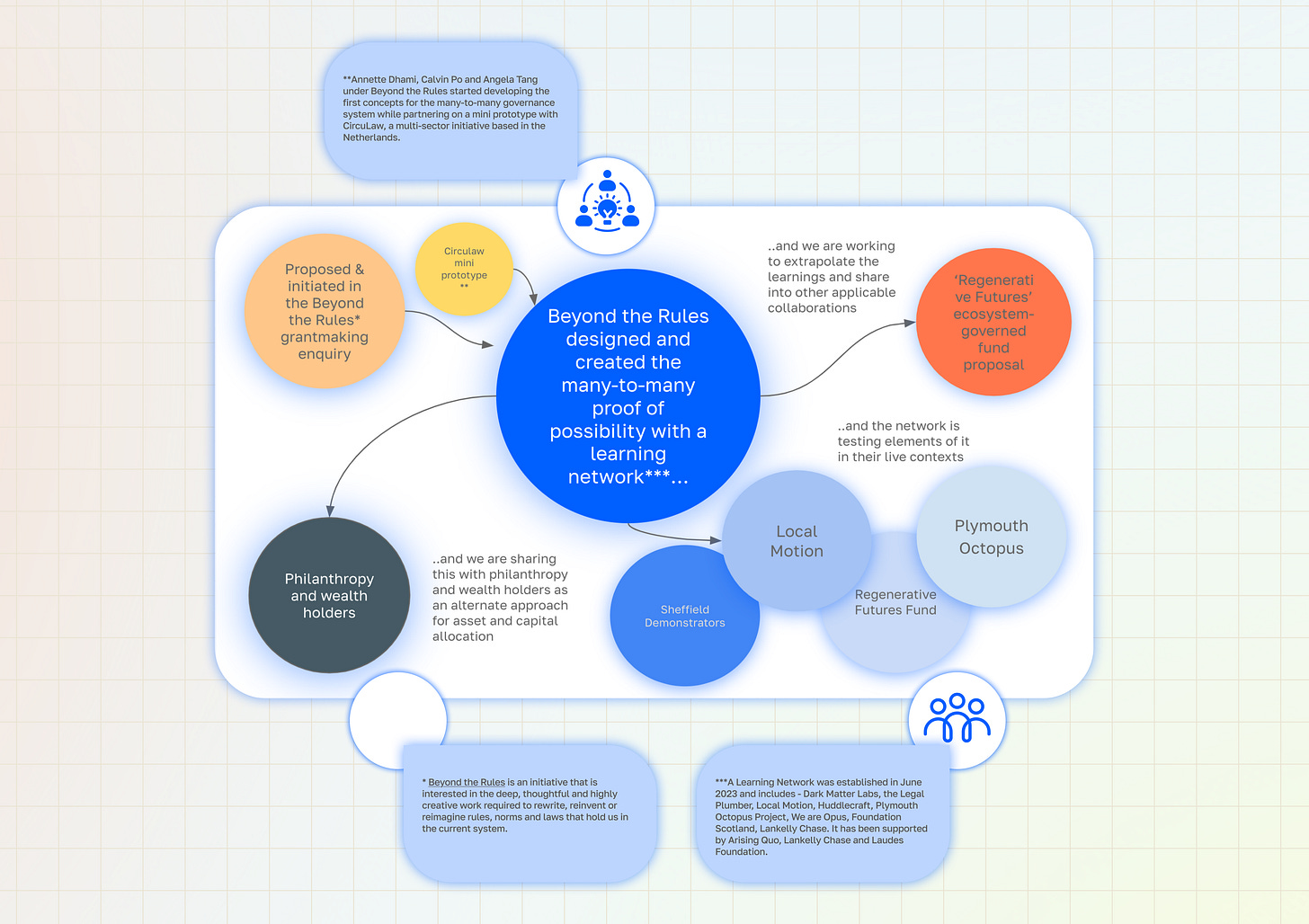

Today, we’re taking a step back to look at the foundational methodology behind this entire initiative. How do you go about creating new models for collaboration when no blueprint exists? Our approach has been a “proof of possibility” — a live experiment where we, along with our ecosystem of partners, served as the primary test subjects.

In this post, the initiative’s co-stewards, Michelle and Annette, discuss the profound challenges and unique learnings that come from trying to build the plane while flying it.

Michelle: We wanted to reflect on the “proof of possibility” we ran, where we essentially decided to live prototype on ourselves with a small group of partners in a Learning Network. While it sounds simple, we learned it’s incredibly complex. You’re making decisions and sense-making within a specific prototype, but you’re also constantly trying to translate those learnings into something more generalised and applicable for others. In many ways, it’s a cool, experimental way of working, but it was also a bit of a nightmare.

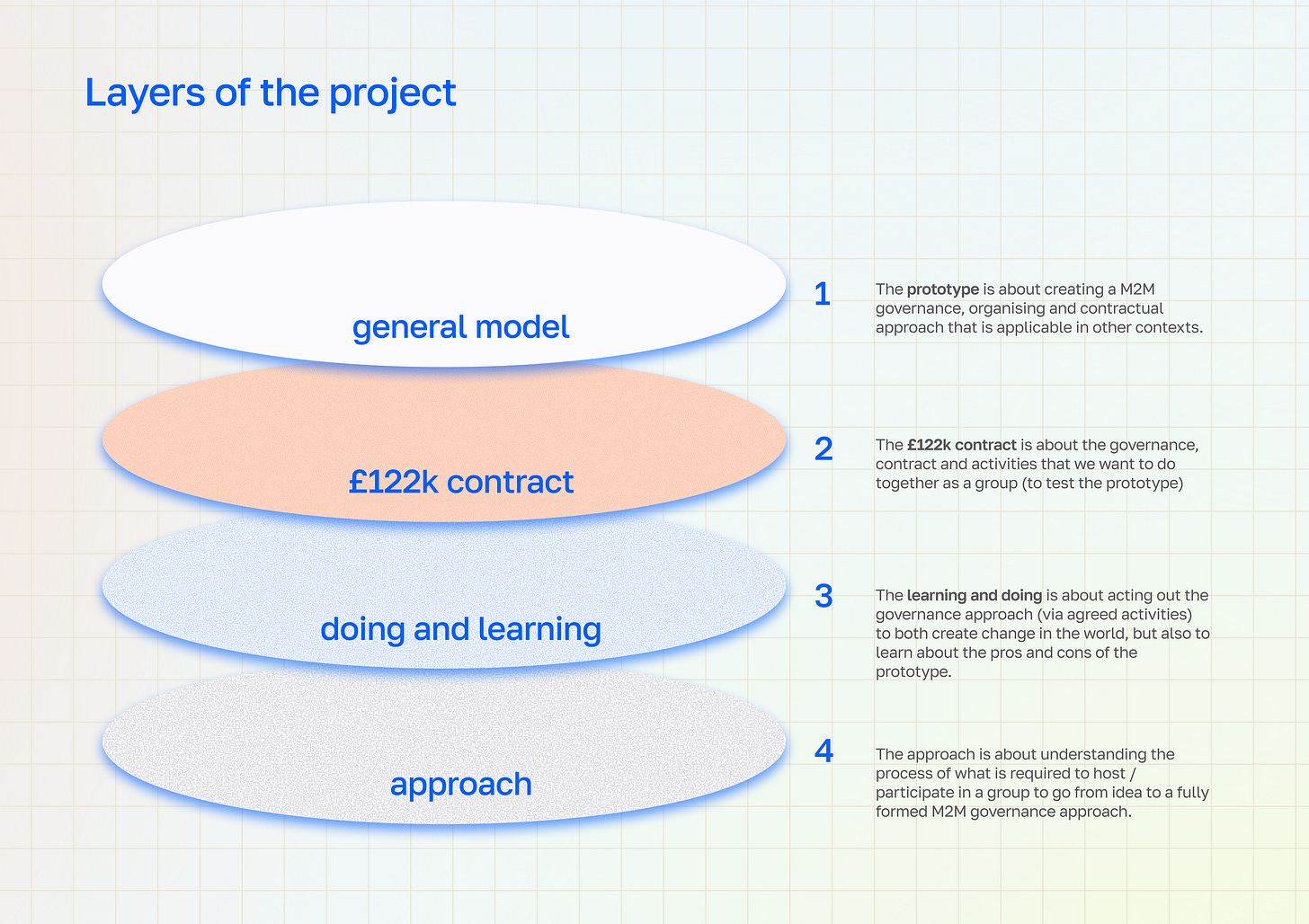

Annette: It was very meta. In this proof of possibility, one of the things we were testing was a learning infrastructure for the ecosystem itself. So you’re testing learning within the experiment, while also prototyping the experiment, and then you have to step back and ask: what did we learn from this specific context versus what is context-agnostic and applicable elsewhere? Then there’s another layer: what did we learn about the wider external landscape and its readiness for this work? And finally, what did we learn about the process of learning about all of that? There’s this feeling of learning about learning about learning.

It’s representative of the fractal nature of this work. For instance, we were a core team working on our own governance while simultaneously orchestrating and supporting the ecosystem’s governance. The ecosystem itself was then focused on building capabilities of the system for many-to-many governance. It was navigating so many layers. On one hand, this has immense value because you’re looking at one question from multiple angles at once. On the other hand, it has been incredibly cognitively challenging.

Michelle: It’s that old adage of trying to build the plane whilst flying it — except there are no blueprints for the plane. I think the complexity we bumped into is probably present for anyone trying to do this kind of work, because everyone has to work at fractals all the time. So I was thinking, what are some things we bumped into, and how did we overcome them? The first breakthrough that comes to my mind was when we started to explicitly ask, “Are we talking about this specific prototype right now, or are we talking about the generalised model?” Just having that clear distinction, a shared vocabulary that the whole learning network could use, was a huge moment of alignment for us. It gave people a way to see we were working on at least two layers at the same time.

Annette: Yes and we found that the difference in thinking required for each of those layers was huge. Thinking through the specifics of what we did in one context versus pulling out principles applicable across all/any contexts was such a massive gear shift. Turning a specific example — “here’s something we tried” — into a generalised tool — “here’s something useful for others” — was probably a five-fold increase in workload, if not more. The amount of planning and thinking required was significantly different.

Michelle: What else comes up for you from this experience of prototyping on ourselves?

If nothing comes to mind, I can jump in. For me it was the dynamic of being the initiators. We were the ones who convened the group and set the mission. In these complex collaborations, the initiator tends to hold a lot of relational capital, power, and responsibility. This was exacerbated because we were managing all these different layers of learning. It centralised the knowledge and the relational dynamics back to us. If one of us was missing from a budget conversation, for example, it was difficult for others to proceed. For me, the bigger point is that to do good demonstration work, it has to be experimental and emergent. But that doesn’t come for free; it has downsides. This re-centralisation was one of them, and it was a lot for us to hold.

Annette: That makes me wonder if a certain degree of that centralisation is inevitable in organising for these kind of ‘proof of possibilities’. When something is this complex and emergent, you can only distribute so much, so early. To meet the real-time needs of the collaboration, you need an agile core team. This is where it gets interesting — we were operating in the thin space between a sandbox environment and a live context. It had to be a genuine live context for people to want to participate, but it was also a sandbox for testing the general model. You have to meet the timelines of the live context; you can’t just pause for six months to work out team dynamics, or the collaboration collapses. So you almost need a team providing strong leadership to hold both realities at once.

Michelle: So, would you do it the same way again?

Annette: I think if we did it again, the things we’ve learned would make it smoother. We’d be more explicit from the start about which layer we’re discussing. We’d have a better sense of how to capture live learning and translate it into a model as we go. When we started, most of our attention was on hosting the live context, and a lot of the synthesis happened afterwards. Having done it once, I’d be more conscious of doing that synthesis in real-time — though the cognitive lift to switch between those modes is still immense.

Michelle: I agree, I would do it again with those additions. The other thing is that when we started, we didn’t even really have the process that we wanted to go through. Now we do. We’ve learned more about what works. Starting fresh, we would have a decent sketch of a process to begin with. Not perfect, and you still have to wing it, but it’s a good start. I’d be interested to do it again and see what happens.

This meta-reflective process — learning about learning while doing — has been a central part of the Many-to-Many initiative creating a ‘Proof of Possibility’ as a way to learn about what’s possible at a system level. While navigating these fractal layers is cognitively demanding, it’s what allows for true emergence, distinguishing this deep, systemic work from simple chaos. It is a messy, challenging, and ultimately fruitful way to discover what’s possible.

In the Many-to-Many website [coming soon] you will find some resources based on what we did in the Proof of Possibility (Experimenter’s Logs and example methods and artefacts like the Contract) and some based on what might be applicable across contexts (a Field Guide, some tools and an overview of System Blockers we’ve encountered) along with case studies and top tips from other contexts in the learning network.

Thanks for following our journey. You can find our previous posts [here], [here] and [here] and stay updated by joining the Beyond the Rules newsletter [here].

Visual concept by Arianna Smaron & Anahat Kaur.