Unlocking the Value for Urban Nature: An Economic Case for Street Tree Preservation in Berlin

Valuing the Ecosystem Services of street trees in Berlin to inform the strategic development of the extension of the M10 tram line

This blog article provides an overview of the joint efforts undertaken in partnership with the District Office Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf of Berlin, The Nature Conservancy in Europe gGmbH, DorfwerkStadt e.V., and Politics for Tomorrow / nextlearning e.V.

Nature often has to pave the way for the expansion of the city’s urban infrastructure. But what if we could more accurately understand the value tree, so we can make a stronger case for decisions that reduce tree removal?

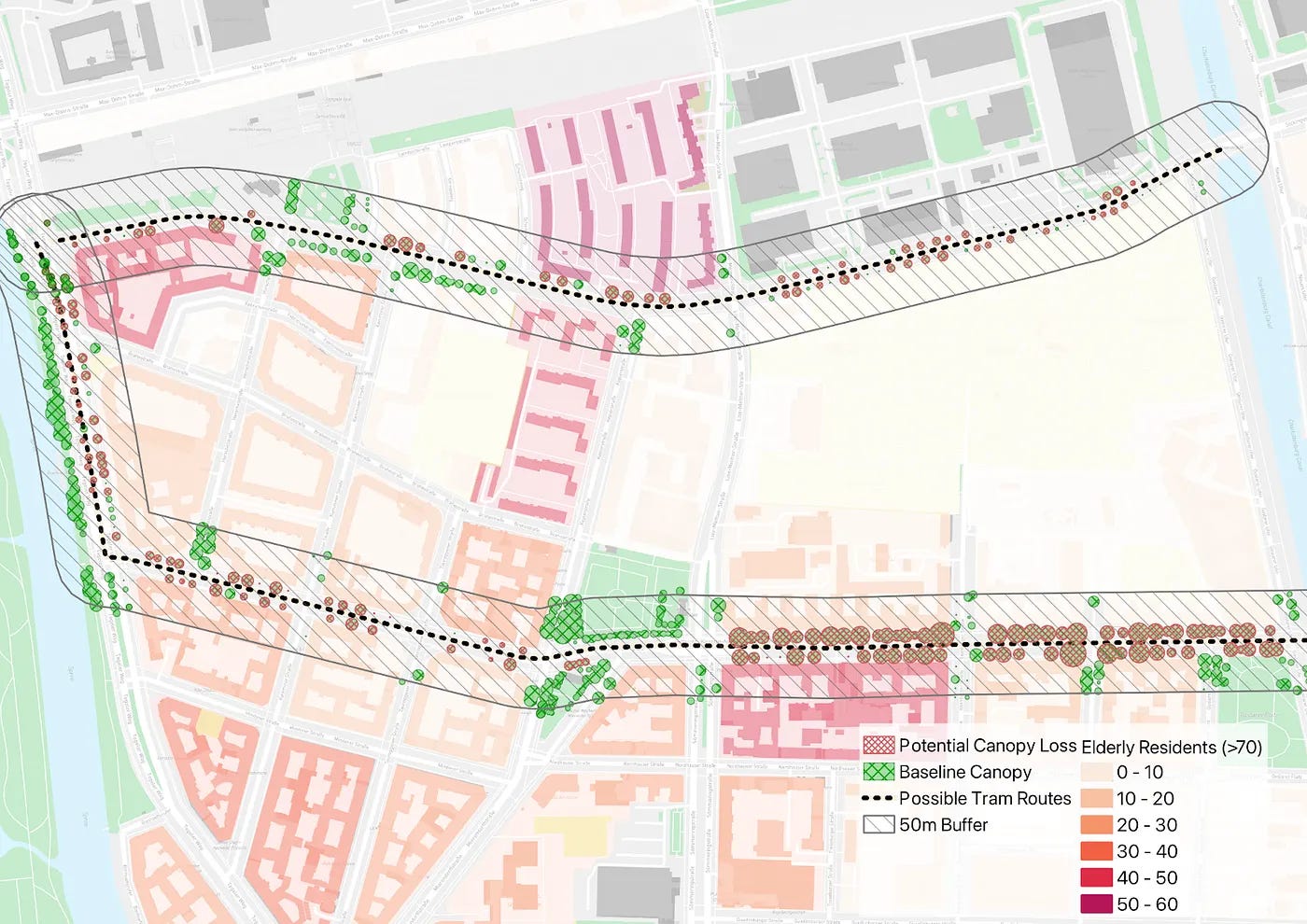

Tram route options and baseline canopy cover

This map shows two tram route options in the urban area, overlaid with baseline canopy cover data:

A red dotted line represents planned Tram Line M10 (New Tram Extension). It spans from Kaiserin-Augusta-Allee through Mierendorffplatz, Osnabrücker Straße, and ends at Tegeler Weg.

The alternative tram route is shown as a magenta dashed line, running through Gaußstraße and Obersstraße.

As Berlin advances its commitment to sustainable mobility, the planned extension of tram line M10 between Turmstraße and S+U Jungfernheide illustrates a familiar urban dilemma: progress at the cost of nature, the tram extension risks removing over a hundred mature street trees. Trees constantly provide a variety of benefits to the citizens around them. As built infrastructure expands, it’s easy to forget the invisible nature systems already at work: cooling our streets, cleaning our air, managing stormwater, and supporting our mental and physical health.

This is where ecosystem services valuation comes in, by quantifying the benefits trees provide, we can integrate ecological assets into infrastructure planning, allowing decision-makers to balance new infrastructure with the natural capital we already have.

A tool to value urban nature

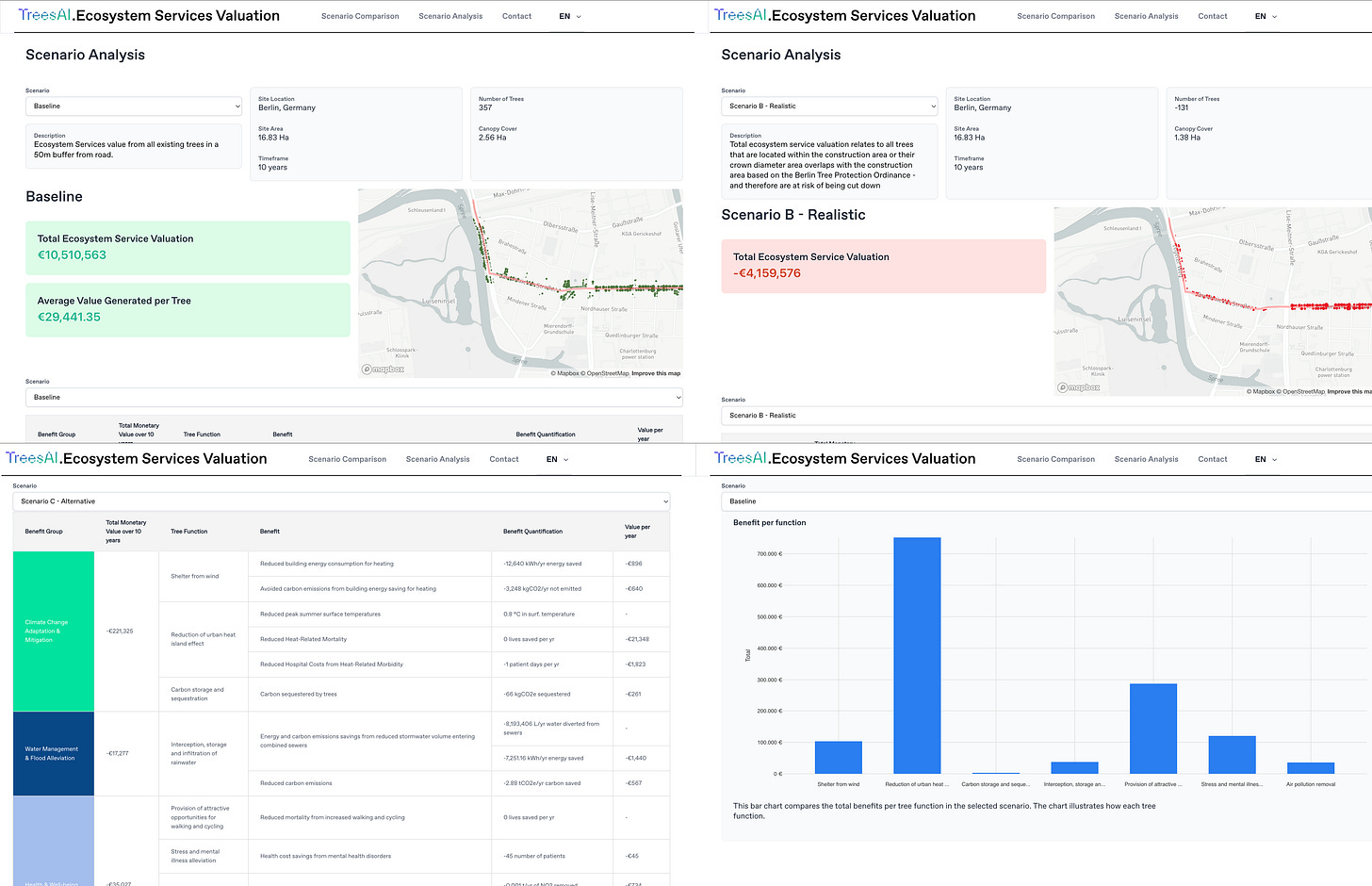

To address this gap, the district council of Berlin Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf and The Nature Conservancy in Europe commissioned our Trees as Infrastructure team to develop and deploy an Ecosystem Services Valuation Tool for the affected Mierendorff Island sites in Berlin. This tool translates ecological functions into benefits and, consequently, into economic metrics, thereby assigning a value to nature within financial and planning systems.

The model assessed ecosystem services within a 50-meter buffer along the tram route, focusing on quantifiable benefits in three key areas:

Climate Adaptation & Mitigation: shelter from wind, temperature moderation and carbon sequestration

Water Management & Flood Alleviation: rainfall interception and stormwater reduction

Health & Well-being: stress reduction, air quality improvements, and support for active lifestyles

To calculate these values, our model leveraged a combination of diverse local data, including high-resolution tree canopy data, detailed meteorological information, and socioeconomic demographics for Berlin. The economic value was derived by applying established valuation methods such as avoided damages (e.g. quantifying the benefits of climate regulation and flood mitigation), market prices (e.g. for carbon credits), and replacement costs (e.g. for water quality improvements). To support these calculations, we use established tools and frameworks, including GI-VAL, B£ST, and InVEST.

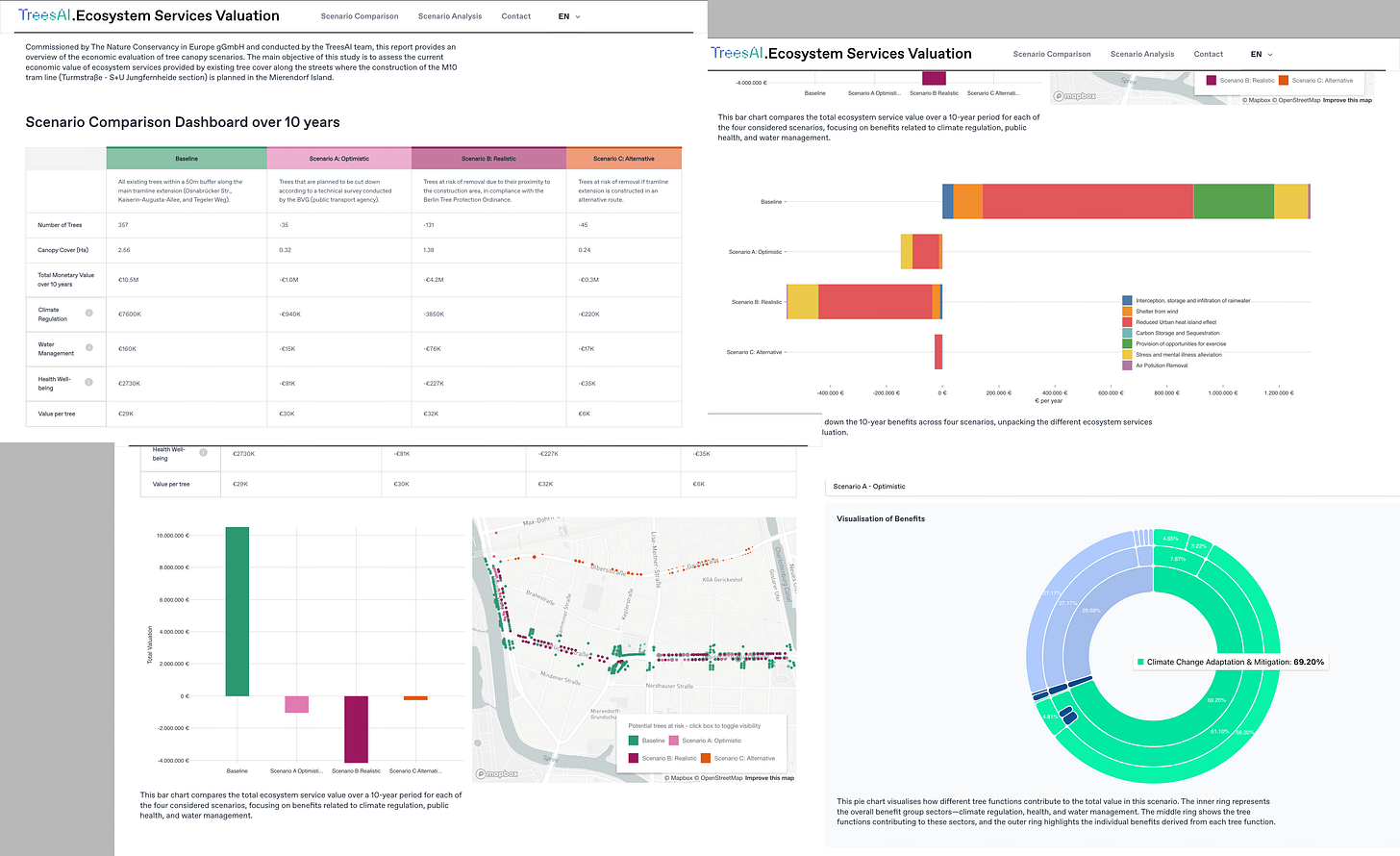

We also developed a web interface for this tool so that the results could be easily shareable and accessible to a broad audience. Designed to reflect the transparency of traditional financial asset dashboards, the Ecosystem Services Dashboard enables users to explore the data in depth: they can adjust scenarios, compare outcomes, and zoom in or out on the map, encouraging a hands-on, investigative approach.

Risks and model limitations

Our model offers valuable insights into the economic contributions of urban trees and their ecosystem services. Like any innovative tool, it has boundaries, best understood as invitations for further exploration rather than flaws.

Its accuracy depends on data quality; incomplete inputs can lead to misestimations, underscoring the need for robust local data. As with many valuation tools, our model simplifies complex natural systems to yield actionable insights, though it may not capture site-specific nuances such as microclimates or tree placement. It currently assumes a linear relationship between services and benefits, while real ecosystems often exhibit non-linear dynamics and tipping points — areas for future refinement.

Then there’s the challenge of putting a price tag on nature. Valuing public commons like clean air or carbon storage remains challenging without standard market prices. Even so, indicative estimates help make the benefits of healthy ecosystems visible in policy and planning. While individual trees generate limited carbon credits, their collective impact and co-benefits are significant at scale.

Systemic shifts such as climate change, policy changes, or technological disruption, are not yet modeled but represent critical frontiers. While we focus on economic benefits, the model does not yet capture social and cultural values that communities attribute to urban green spaces or account for social vulnerability, such as how the loss of trees might disproportionately affect low-income or elderly residents.

In this light, the model is best used as one valuable piece in a broader puzzle — most powerful when combined with local expertise and qualitative insights to establish a more responsible, evidence-informed decision-making approach for urban resilience.

Our key findings

When considering the three benefit groups on climate regulation, water management and health, the main findings for the baseline situation of the standing trees as they are today were:

Baseline value: At the baseline scenario site, the total value of ecosystem services provided by all currently standing trees located within 50 metres of the road over a 10-year period is estimated at €10.5 million. This equates to an average economic value of €29,440 from ecosystem services per tree over the same period.

Our model was then used to explore three distinct scenarios to compare the potential impact of tree removal:

‘Optimistic’ scenario: Relates to the removal of the 35 trees identified in a technical survey commissioned by the BVG (Berlin’s public transport agency) were removed, the projected ecosystem services loss would be approximately €1 million over a decade.

‘Realistic’ scenario: Relates to the removal of 131 trees, which are those at risk of being felled as their crown diameter overlaps a certain buffer distance from the future tram line, leading to an estimated loss of approximately €4.2 million in value over a decade.

‘Alternative’ route scenario: Relates to the removal of 45 trees if the tramline was built along an alternative route, resulting in a projected loss of approximately €300,000.

Although the alternative route maintains a canopy cover similar to the optimistic scenario, its economic impact on ecosystem services is notably lower. This difference largely comes down to a few important factors. The trees along the alternative path tend to be smaller, so they naturally provide fewer benefits like carbon capture, cooling, and air purification. Secondly, this route passes through an area with much fewer residents, meaning trees contribute less to direct health benefits such as stress relief, improved air quality and encouraging outdoor activity. Also, with fewer buildings and residents exposed to wind currents, the climate regulation benefits per tree are less relevant.

This highlights a key insight for planning: the impact of a tree in a city is highly dependent on its specific context, what surrounds it, how many people it benefits, the local environmental risks, and how much the urban system relies on it to cope with those risks. Not all trees have the same value, and understanding their place within the urban fabric is key to making decisions around preserving urban nature and maximising ecosystem services.

What does this mean for city stakeholders?

The numbers in this study reveal a critical opportunity: urban trees are not just passive greenery but invaluable infrastructure delivering vital ecosystem services — carbon capture, air purification, cooling, stormwater management, and community well-being — that currently go unpriced and underleveraged. This structural blind spot means cities miss a chance to unlock new financing pathways that could transform how living ecosystems are maintained and expanded.

Imagine innovative financing frameworks that monetise the ecosystem value of existing trees to directly funnel resources into city households. The beneficiaries of these ecosystem services include municipal enterprises managing energy and rainwater systems, municipal housing associations, and private companies seeking to improve their sustainability profiles and creditworthiness with banks. These stakeholders could contribute to a new funding mechanism, reflecting the shared value trees provide across urban sectors. These funds could then be allocated to enhance tree maintenance, ensuring the health and longevity of the urban canopy, while simultaneously financing targeted climate adaptation measures in vulnerable areas of the district.

To support this vision, city policies must evolve:

Empower subsidiarity and support local initiatives by formally recognising the community’s active stewardship role in caring for and maintaining urban nature.

Strengthen tree protection ordinances by setting stricter tree replanting ratios (e.g. 1:5 or 1:10) and fines proportional to the projected ecosystem service losses over 10–20 years, using our study — which translates these services into monetary value — as the foundation for accurately accounting the time lag and diminished benefits between a felled mature tree and its young replacement.

Redesign compensation frameworks to go beyond tree replacement, enabling funds to be channeled into additional appropriate interventions (e.g. unsealing, rain gardens) that respond to site-specific adaptation needs.

This case in Berlin reinforces a critical insight on the need for coordinated urban planning: housing and urban development, climate adaptation, and transport transitions must be designed as interconnected systems. Without such integration, we risk implementing climate solutions that deliberately undermine the very resilience we aim to build.

On March 22 2025, our findings were formally presented by one of our team member Sebastian Klemm, to a broad audience, including the public, political representatives, and notably, district council leads from civil engineering, green space and climate adaptation. As a result of this engagement, our tree ecosystem valuation study is being used by the district councillor to support the renegotiation of all elements of the project, including the tram line extension, its planning alternatives, proposed route, the calculation basis for compensation measures, and their intended purpose.

Looking ahead

The results of this study reveals the significant, long-term societal losses that would result from removing these mature trees to extend the M10 tram line. This local tension of transport infrastructure developing versus the protection of nature that regulates our microclimate, mirrors a wider urban planning dilemma faced by cities across Europe and beyond on how to align societal development with ecological and societal resilience.

This case points to a larger strategic question:

How can infrastructure planning be reoriented to systematically reflect public health, climate resilience, and the long-term well-being of communities in legal and fiscal decisions?

This question shaped the expert dialogue on June 20th 2025, curated and convened by Politics for Tomorrow / nextlearning.eu in collaboration with the Trees as Infrastructure team, DorfwerkStadt e.V., and the Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf district office. The working session marked a critical step in turning the study’s findings into actionable governance frameworks. Building on the earlier public presentation, this closed session provided a platform for cross-sector reflection and collaborative policy design. By integrating ecological, health, and economic insights with legal and administrative expertise, the session enabled a shared understanding of trees as living infrastructure, emphasizing their value not just in compensation terms but within proactive planning and investment strategies.

Most importantly, this dialogue laid the foundation for systemic change, shifting from fragmented responsibilities to cooperative governance, and from isolated environmental mitigation to integrated, health-oriented resilience policies. Ideas for a coordinated collaboration strategy emerged, including piloting new planning and financing models on Mierendorff Island, embedding the valuation approach into Berlin’s compensation guidelines, and developing governance tools like a Commons Index and local operating models to unlock cross-sector investment.

The outcomes of this dialogue offer immediate policy relevance:

Proposals for adapting the M10 route planning based on comprehensive ecological and social valuation;

A replicable citywide model for integrating ecological and health data into infrastructure decisions;

A framework for embedding green infrastructure value into the planning and budgeting strategies of the district, Senate, and both public and private institutions;

An alternative to outdated cost-benefit tools like the Koch method, which continues to treat trees as depreciable assets, instead recognising their full ecological, social, and economic value as resilient, multi-solving elements.

If you are working to build cities that are equitable and ecologically sound, this is your invitation: Join us in advancing a movement for living infrastructure — where urban trees and nature are not obstacles to progress but essential infrastructure for urban resilience and liveable cities.

Full Report: Dive into the complete findings, data, and methodology in the ecosystem services valuation report > Link to PDF

Interactive Dashboard: Explore the spatial distribution and value of Berlin’s tree canopy via our Ecosystem Services Dashboard.

Partners: District Office Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf of Berlin, The Nature Conservancy in Europe gGmbH, DorfwerkStadt e.V., and Politics for Tomorrow / nextlearning.eu

Team: Sofia Valentini, Sebastian Klemm, Chloe Treger, Gurden Batra, Caroline Paulick-Thiel

TreesAI identity created by Arianna Smaron

Love this. Subscribed for more. I see this work as part of the seeds of a world where trees aren’t a secondary part of urbanity, but once again the primary structure… https://open.substack.com/pub/earthstar111/p/dreaming-of-flying-with-my-descendants?utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web