Where to next? Five pathways for a regenerative built environment

Possibilities for the Built Environment, part 2 of 3

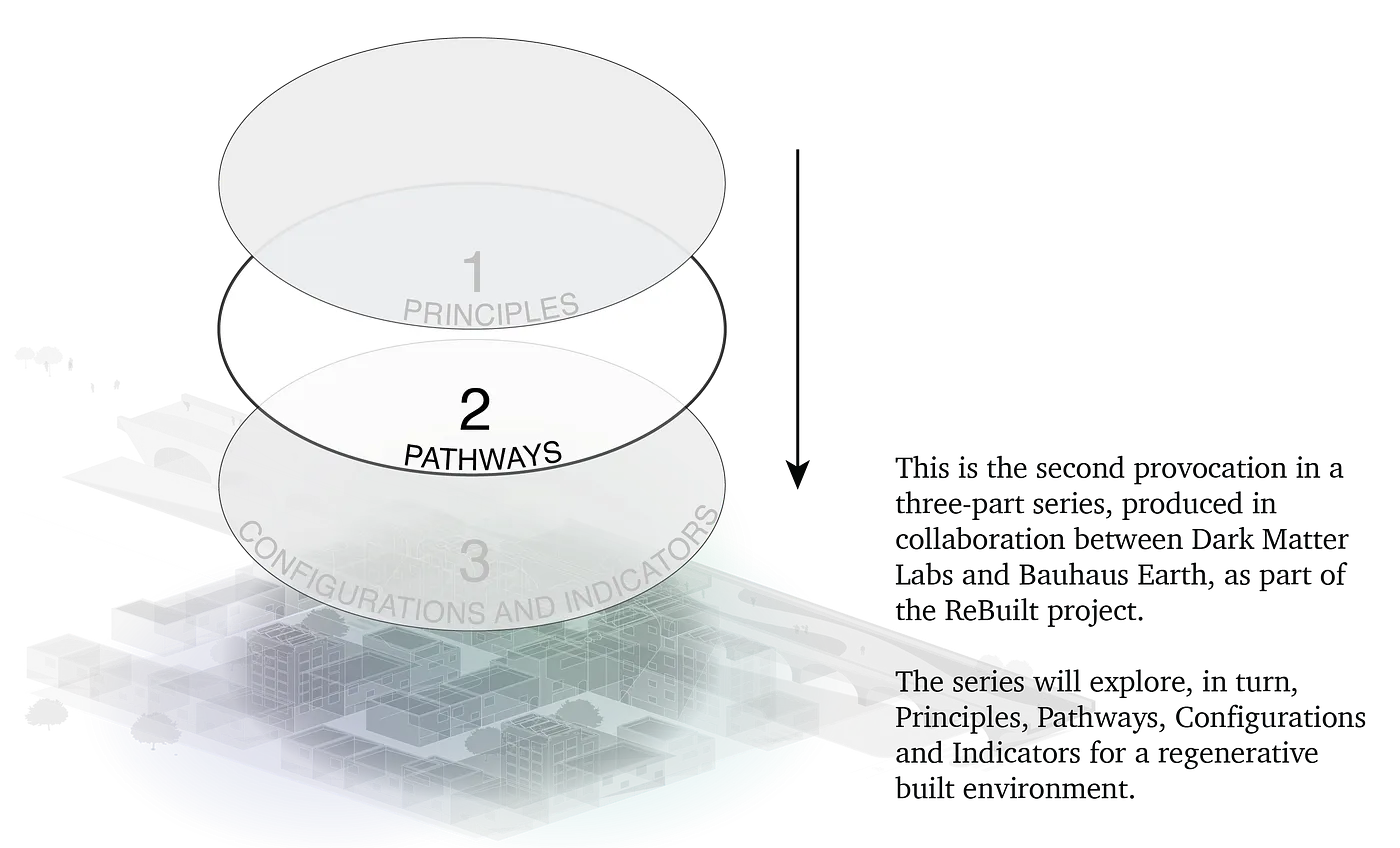

This is the second in a series of three provocations, which mark the cumulation of a collaborative effort between Dark Matter Labs and Bauhaus Earth to consider a regenerative future for the built environment as part of the ReBuilt project.

In the first piece, we suggested how six guiding principles for a regenerative built environment could redirect our focus. In this piece, we lay out six pathways toward regeneration, with suggested benchmarks and possible demonstrators, as a means of starting conversations, and identifying allies and tensions. The final piece in the series uses the configuration of the cement industry to explore the idea of nested economies and possible regenerative indicators.

Toward a process-based definition of regeneration

This piece leans into the friction between today’s extractive norms and the regenerative futures we have yet to realise.

We propose five pathways to establish regenerative practices throughout the built environment: these will span scales and sectors while driving change aligned with the principles laid out in the previous provocation. These pathways represent five modes for developing a multiplicity of new metrics, as well as creating the conditions for further progress to be taken on by future generations. Embedded in this logic are multiple and diverse systemic entry points for various actors to engage along the way.

These pathways are directions of travel that can be launched within the current economic system, without adopting a solution mindset. However, there are still real challenges to progress because of today’s political economy and scale of the polycrisis. While these pathways can be initiated within the current economic system, to be fully realised they must transform the system itself along the way.

One aspiration for these pathways is that they can capture the imagination and energies of a range of stakeholders, by creating containers for the changes it will take to bring us to a regenerative built environment. If we assume that to reach this future we will need both paradigm-shifting ‘impossible’ ideas and real demonstrations of best practices within our current contexts, then these pathways can hold together the different strands of effort, from the more feasible to the boundary-pushing, in one directional container. In each pathway, we ourselves look toward collaborators across geographies and disciplines to imagine, visualise and orient ourselves toward where these shifts could take us, in 2030, 2050 and beyond.

On a pragmatic level, structures to support initiation and governance of these pathways already exist and can be further fostered. Ownership for pathways can sit at the city or municipal level, supported by city networks such as Net Zero Cities, C40 cities and others, and further enabled through multi-municipal or regional coalitions to reach national scales. This type of multi-scalar, integrated approaches to the pathways can create the conditions for bottom-up schemes and ideas in communities and allow these to grow. The scale and pace of the transition we need requires governing decision-makers to have visibility over exceptional ideas that can push at the edges of the Overton window.

These pathways are not wholesale solutions to the problem, but rather provocative visions to incite discussion, draw out coalitions, grow a sense of responsibility and build momentum. It’s not that if we do these five things that a regenerative future will be reached. Rather, these are components of a re-envisioning.

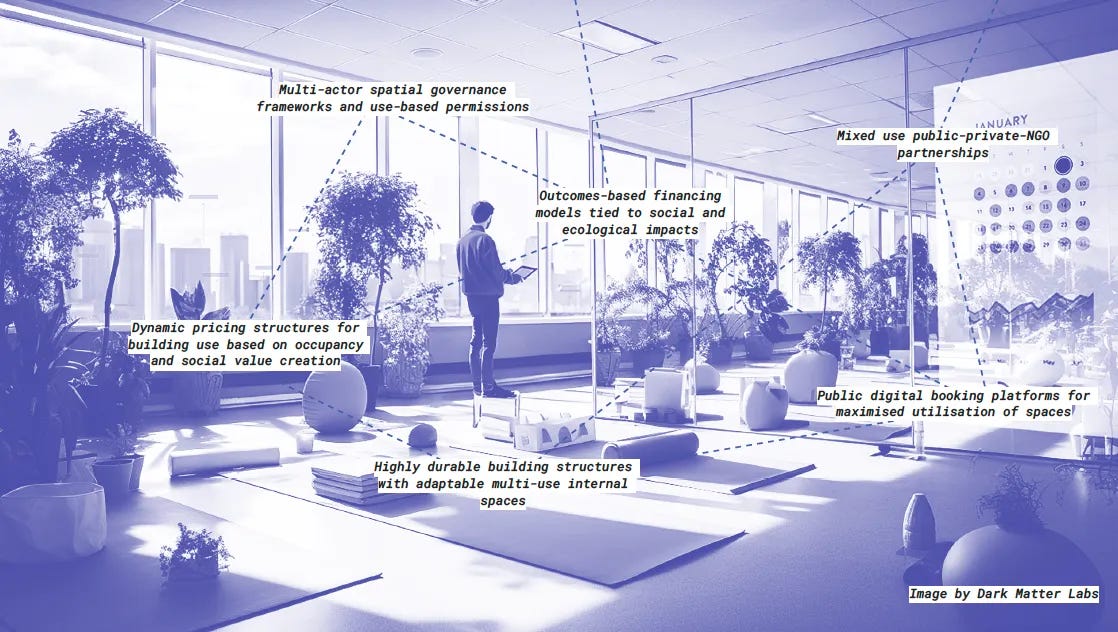

Pathway 1: Maximising utilisation

Maximising the utilisation of our existing resources, spaces and infrastructures is one of the most transformative actions we can undertake in a context of resource shortage, carbon emissions crisis and labour crisis. That is especially relevant in the European context where our resource and space use inefficiencies are massive. Unlocking this latent capacity promises significant advancements in social justice and decoupling space and use creation from extraction and pollution. This develops a range of strategies from full utilisation of existing building stock, sharing models, flexible space use, with instruments such as open digital registries, smart space use platforms, smart contracts, and the like.

Deep structural changes in mechanisms to challenge speculative land markets and reform regulatory frameworks will be needed to embed redistributive and democratic principles into the governance of urban space.

Potential challenges:

The implementation of maximal utilisation is severely constrained by today’s profit-driven development logic, which prioritises profit through new development and property speculation over efficient or shared use. Institutional inertia, entrenched ownership regimes and the financialisation of housing all work against such a shift, while digital tools like registries and smart contracts risk reinforcing existing inequalities if not democratically governed.

System demonstrator: reprogramming office buildings from 35% to a 90% use, increasing financial flows of the building

What could this look like in 2050?

Multi-actor spatial governance frameworks and use-based permissions

Dynamic pricing structures for building use based on occupancy and social value creation

Highly durable building structures with adaptable multi-use internal spaces

Outcomes-based financing models tied to social and ecological impacts

Mixed use public-private-NGO partnerships

Public digital booking platforms for maximised utilisation of spaces

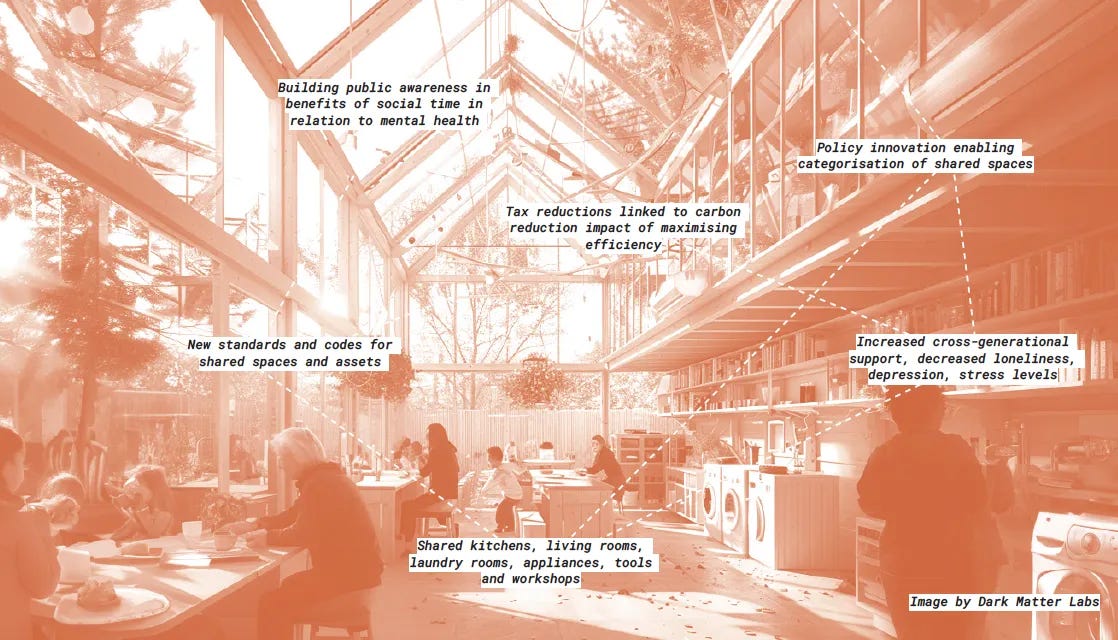

Pathway 2: Next-generation typologies

Next typologies are no longer governed by the principle that form follows function. Instead, they transcend traditional asset classes based on programmatic use, as a new asset class valued for the optionality, flexibility, use efficiency and value creation they provide. Decoupling value creation from extraction, systemic inefficiencies and carbon emissions here happens through focusing on social capital–for instance, radical sharing and cooperation models, as well as intellectual capital–as new innovation models and new design typologies.

Without directly challenging speculative land markets, financialisation, and the classed and racialised histories embedded in built form, next-generation typologies may risk becoming a greenwashed evolution of the status quo rather than a transformative departure from it.

Potential challenges:

In capitalist urban systems, typologies and asset classes are produced through financial logics, property relations and commodification. Reframing buildings as flexible, innovation-driven assets may simply reproduce these dynamics in a new guise, reinforcing speculative value creation and market discipline under the banner of sustainability.

System demonstrator: Community living rooms–lightweight extensions on existing buildings, providing amenities with the right to use

What could this look like in 2050?

Building public awareness in benefits of social time in relation to mental health

New standards and codes for shared spaces and assets

Tax reductions linked to carbon reduction impact of maximising efficiency

Shared kitchens, living rooms, laundry rooms, appliances, tools and workshops

Policy innovation enabling categorisation of shared spaces

Increased cross-generational support, decreased loneliness, depression, stress levels

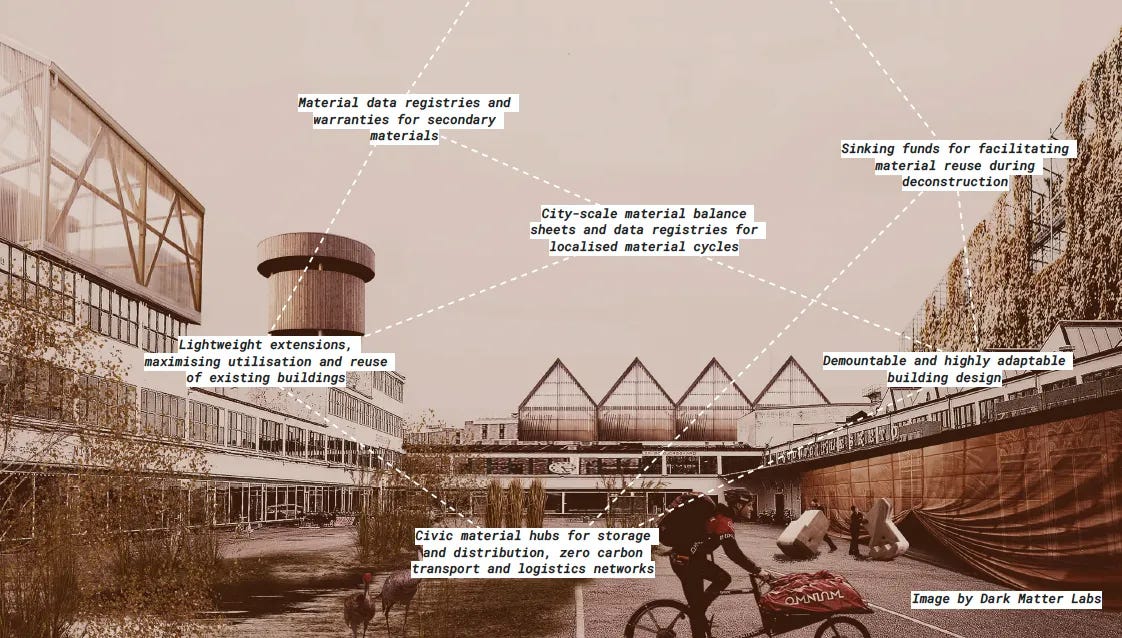

Pathway 3: Systems for full circularity

Even though we have comprehensive knowledge on circularity, current levels in Europe are extremely low, and globally its rate is declining, thus this work focuses on the systems unlocking it and instruments driving its advancement on the ground. Apart from a comprehensive understanding of the craft (design for disassembly, development of city-scale material components networks, use of non-composite materials), we need the institutional economy and systems enabling circularity. That includes instruments such as material registries, material passports, financing mechanisms, design regulations, all developed simultaneously to unlock the new systems for circularity.

For circularity to be genuinely transformative, it must be accompanied by political and economic restructuring — challenging the growth imperative, redistributing material control, and embedding democratic governance into how urban resources are managed and reused.

Potential challenges

Structural barriers hinder circularity. Extraction, planned obsolescence and short-term profit maximisation, which are the main imperatives in the current system, actively disincentivise long-term material stewardship. Circular practices often require slower, more localised and collaborative modes of production, which clash with the logics of global supply chains, speculative development and financialised real estate.

Moreover, without addressing issues of ownership, labour relations and uneven access to materials and technologies, circular systems risk being implemented in ways that benefit private actors while offloading costs onto public bodies or marginalised communities.

System demonstrator: City-scale architectural components bank, with developers’ right-to-use models

What could this look like in 2050?

Material data registries and warranties for secondary materials

Lightweight extensions, maximising utilisation and reuse of existing buildings

City-scale material balance sheets and data registries for localised material cycles

Civic material hubs for storage and distribution, zero carbon transport and logistics networks

Demountable and highly adaptable building design

Sinking funds for facilitating material reuse during deconstruction

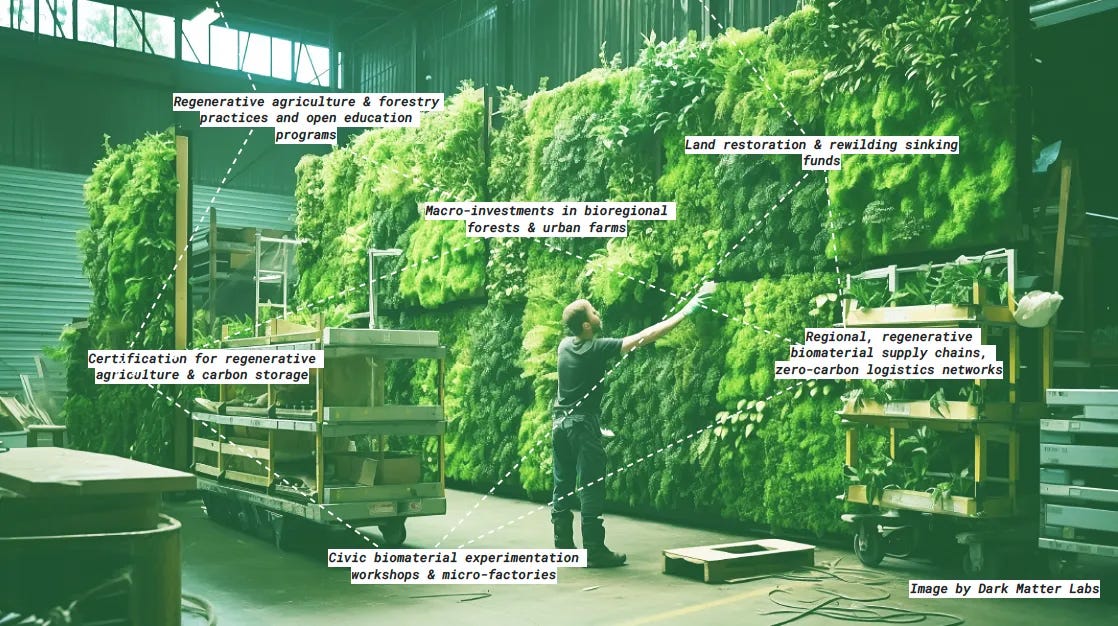

Pathway 4: Biogenerative material economy

The long-term future of our material economy must be bioregenerative. This transition needs deep understanding of systems impacts, avoiding further global biodiversity and land degeneration through green growth. This shift requires a transformation in land use for materials, moving from “green belts’’ to permaculture and regenerative methods, from supply chains to local supply loops. This requires developing new local material forests, zero-carbon local transport, non-polluting construction methods, as well as the policy, operational and financial innovation for a successful implementation of a fully biocompatible material economy.

True transformation will involve challenging capitalist land markets, redistributing land and decision-making power and centering indigenous and community-led stewardship practices within the material economy.

Potential challenges:

We must not underestimate how global capitalism — through land commodification, agribusiness and extractive supply chains — actively undermines regenerative potential. Transforming green belts into permaculture zones, or establishing local material forests, requires not just technical and policy innovation, but a fundamental shift in land ownership, governance and power relations. Without addressing who controls land and resources, and whose interests are served by current material economies, there is a danger that biogenerative strategies become niche or elite enclaves, rather than systemic solutions.

System demonstrator: Neighbourhood gardens of biomaterials for insulation panels components for on site retrofitting

What could this look like in 2050?

Regenerative agriculture & forestry practices and open education programs

Certification for regenerative agriculture & carbon storage

Macro-investments in bioregional forests & urban farms

Civic biomaterial experimentation workshops & micro-factories

Land restoration & rewilding sinking funds

Regional, regenerative biomaterial supply chains, zero-carbon logistics networks

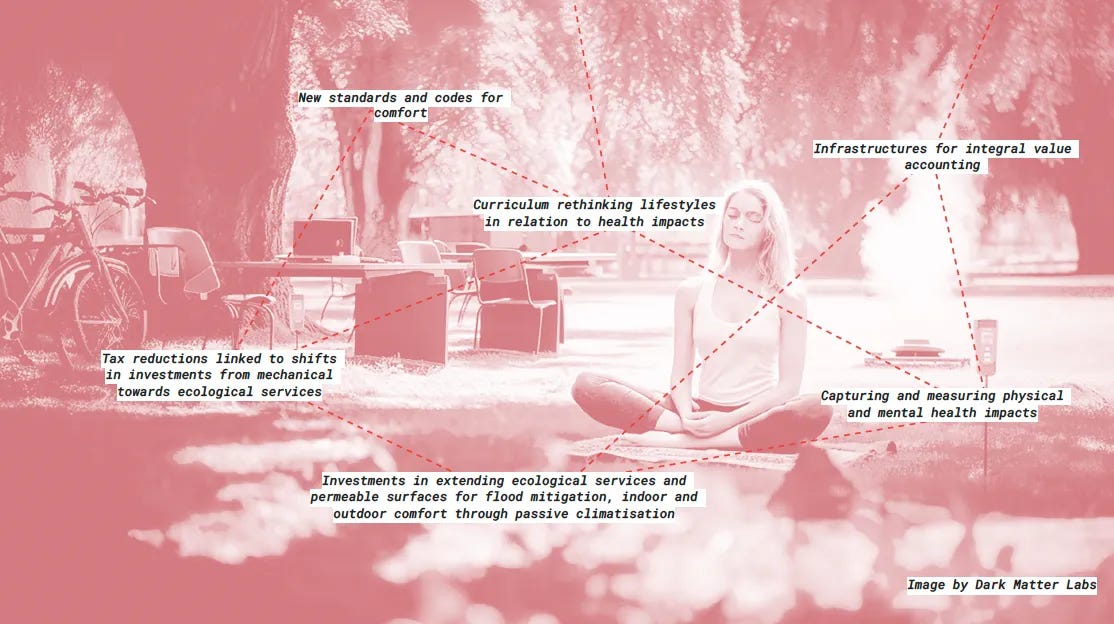

Pathway 5: Shifting comfort, increasing contact

The ways we live in buildings today alienates us from our environmental and earthly context. Today’s built environment is designed to optimise for sterilisation through conditioned environments, separating us from the biomatter that is both input and output to our livelihoods. In providing comfort, we have been depending on extraction of resources, other species, biodiversity and ironically ourselves. We need to decouple the economy of comfort, which is here a shorthand for human-optimised environmental conditions, from extraction and externalisation. Pathways in driving this shift include participation and care models, increasing social values, shifting human relation to nature, a shift from technological to ecological services providing comfort, an increase in social and physical activity, a shift from the building scale to other scales, such as city-scale nature-based infrastructures and micro-scale furniture or clothing.

Real progress will involve confronting the socio-economic systems that produce uneven access to comfort, land and energy, and reconfiguring them through justice-oriented redistribution, democratic urban governance and decommodified approaches to housing and care.

Potential challenges:

In this pathway, we must not romanticise behavioural or cultural change without sufficiently addressing the structural conditions that produce and maintain the current ‘economy of comfort’. The alienation it describes is not simply the result of misplaced design priorities or cultural habits, but of a capitalist system that commodifies comfort, standardises it through global construction norms, and externalises its costs onto ecosystems and marginalised communities. Some people experience the comfort constructed by today’s systems much more than others.

Shifting toward ecological and participatory models of comfort is valuable, but without challenging the political economy that privileges resource-intensive, climate-controlled lifestyles for some while denying basic shelter or agency to others, such shifts may remain symbolic or limited in scope.

System demonstrator: Retrofitting a neighbourhood to new comfort standards to increase this area’s economic resilience to changing energy landscape.

What could this look like in 2050?

New standards and codes for comfort

Tax reductions linked to shifts in investments from mechanical towards ecological services

Curriculum rethinking lifestyles in relation to health impacts

Investments in extending ecological services and permeable surfaces for flood mitigation, indoor and outdoor comfort through passive climatisation

Infrastructures for integral value accounting

Capturing and measuring physical and mental health impacts

More community and individual knowledge about how to deal with the material world, ranging from biomatter to biodegradable consumer goods

Local biowaste sorting and utilisation in industry/agriculture

From a static to a process-based definition of a regenerative future

In viewing our transition to a regenerative built environment through these core shifts, we look toward a process-based definition of what is regenerative. A process-based definition would be an understanding of the regenerative that is calculated not by fixed, profit-driven metrics, determined on the basis of isolated data-points, or tied to particular policy benchmarks, but rather something dynamic, intuitive, and assembled from across knowledge-spheres and perspectives, with their associated means of measurement.

A process-based definition might adapt to the changing data landscape, material reality, technopolitical ground conditions and Overton windows of different contexts. Whereas absolute metrics like embodied carbon are difficult to attain with accuracy, and fail to capture the whole picture, targets pegged to individual points in time and specific standards can quickly become obsolete. A process-based approach is inspired by DML’s Cornerstone Indicators [more information at this link], a methodology which creates composite, intuitive indicators for assessing change over time, co-developed and governed in place.

Originally co-designed with Dr Katherine Trebeck, the Cornerstone Indicators were initiated in the city of Västerås in Sweden to support citizens to co-design simple, intuitively understandable indicators that encapsulate what thriving means to the people of the Skultana district. The indicators, which align with overall goals like ‘health & wellbeing’ and ‘strong future opportunities’, can facilitate greater understanding of a place, enable further conversation, and guide future decisions. The initial 9-month workshop process to design this first iteration of the Cornerstone Indicators, resulted in indicators such as ‘the number of households who enjoy not owning a car’, and ‘regularly doing a leisure activity with people you don’t cohabit with’ which were analysed and offered to local policymakers. The success of this process has led to explorations of the Cornerstone Indicator process across Europe and North America. Initiatives like the Cornerstone Indicators present a model of how momentum toward a regenerative future for the built environment can be built. It’s urgent that we begin using process-based definitions and practices to bring more people to the table and increase the potential for transition pathways to gain traction.

Conclusion

In the first two pieces in this series, we have explored the idea of a regenerative future in the built environment by examining how our current frameworks for regeneration fall short of meeting the demands of the present moment. We outline principles and pathways for charting a course toward genuine transformation.

In providing examples of leading-edge organisations making progress toward a regenerative future, these pieces are intended to invite conversation, feelings of agency and reflection, even in the face of prevailing systemic constraints. Rather than offering neat solutions, this piece seeks to open doors to new possibilities.

The context and projections offered here raise a number of questions. For a wholesale transition, it will be important to understand what will indicate progress toward regeneration, as well as how decisions will be made in order to resist the co-opting of regenerative principles into status quo ways of operating.

The remaining piece in this series will explore:

How configurations of material extraction, labour and monetary capital entrench nested economies and particular power relations, using the example of the cement industry

Possible indicators of progress toward a regenerative built environment, and of the limitations encountered

Together these pieces aspire to introduce the idea of a regenerative built environment and associated promises and challenges, to inspire a sense of direction and to sketch the broader systemic shifts to which we must commit.

This publication is part of the project ReBuilt “Transformation Pathways Toward a Regenerative Built Environment — Übergangspfade zu einer regenerativen gebauten Umwelt” and is funded by the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection (BMUV) on the basis of a resolution of the German Bundestag.

This piece represents the views of its authors, including, from Bauhaus Earth, Gediminas Lesutis and Georg Hubmann, and from Dark Matter Labs, Emma Pfeiffer and Aleksander Nowak.